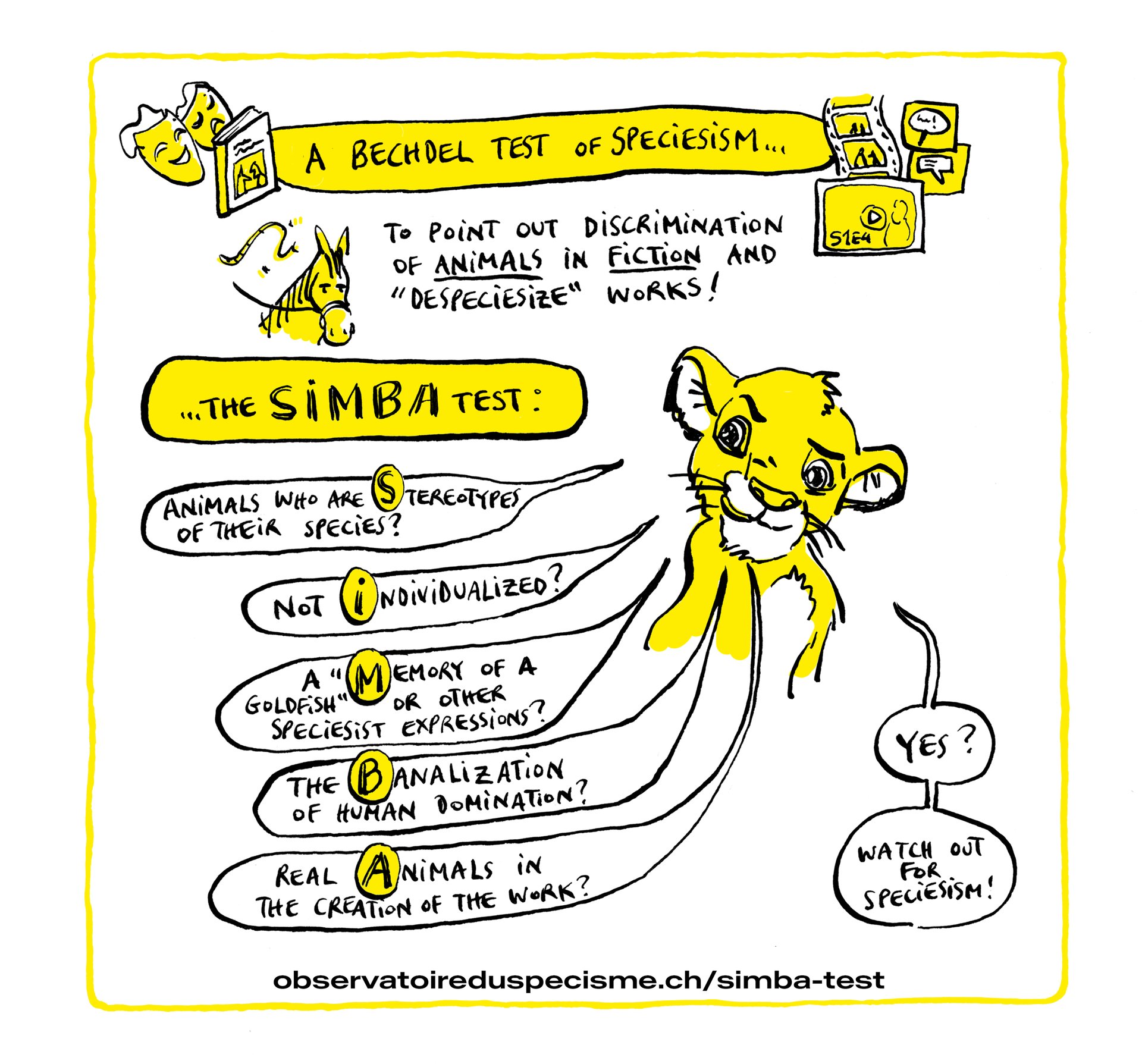

A Bechdel Test of Speciesism (the SIMBA test)

Publié le 29 mai 2024

- By Fanny Vaucher for the Observatory of Speciesism

- Illustrations by Fanny Vaucher

- Translation by Jola Cora

This is a translation from the original article in French

One evening, leaving a funny and poetic play, I thought to myself, as I often do, “It was great, if only there hadn't been that speciesist scene...”. The protagonists were hunting an animal – albeit imaginary – and rode imaginary horses, but the story would have worked just as well without that representation of human domination of animals. The friend who had invited me to this play, and who knew the director, had the same reaction I had when seeing the play and shared it with him. Very concerned about not conveying discriminatory ideas towards anyone, including animals, he thought about it with her and edited his play so as to make it non speciesist. He switched the hunt to a... hunt for mushrooms, and the characters were no longer traveling on any other animals but themselves. This play, which by the way is meant for a young audience, will continue to touch a wide audience, but from now on will show a quest in which no individual is used by another.

This event made me realize that creators of fiction are not necessarily ill-intentioned. They don't necessarily mean to reinforce or trivialize the oppression of other animals. Rare are those who consciously wish to harm animals. They are part of a fundamentally speciesist society and often simply lack the tools and the time to not reproduce this real or symbolic violence. We, activists who have been working and fighting for a long time against this discrimination, who are enthusiasts – and sometimes creators ourselves – of fiction, can propose them an evaluation chart for their creations.

A proposition inspired by the Bechdel test

Named after comic book author Alison Bechdel, this famous test is made of three questions[1] indicating sexism in films. Bechdel and her friend Liz Wallace came up with the idea in reaction to the small number of female characters and their role of foils for male characters. The Bechdel test served as a starting point for me to put problems of speciesist representation in fiction into 5 points. With a double aim:

- to point at and criticize speciesism, which is present everywhere in cultural productions of fiction, and which contributes to anchor the idea that human supremacy is timeless, normal and immutable;

- to help people who wish to create non speciesist works of fiction to evaluate if their creation is in fact harmless to non human animals.

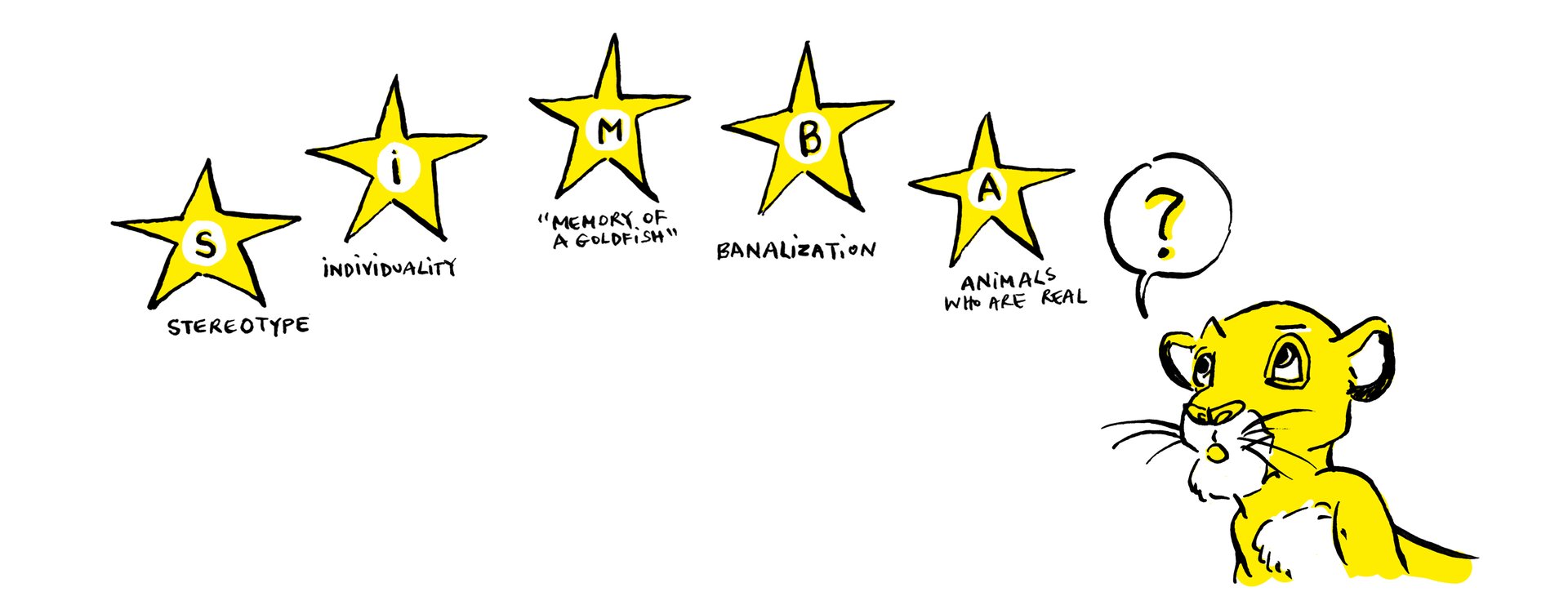

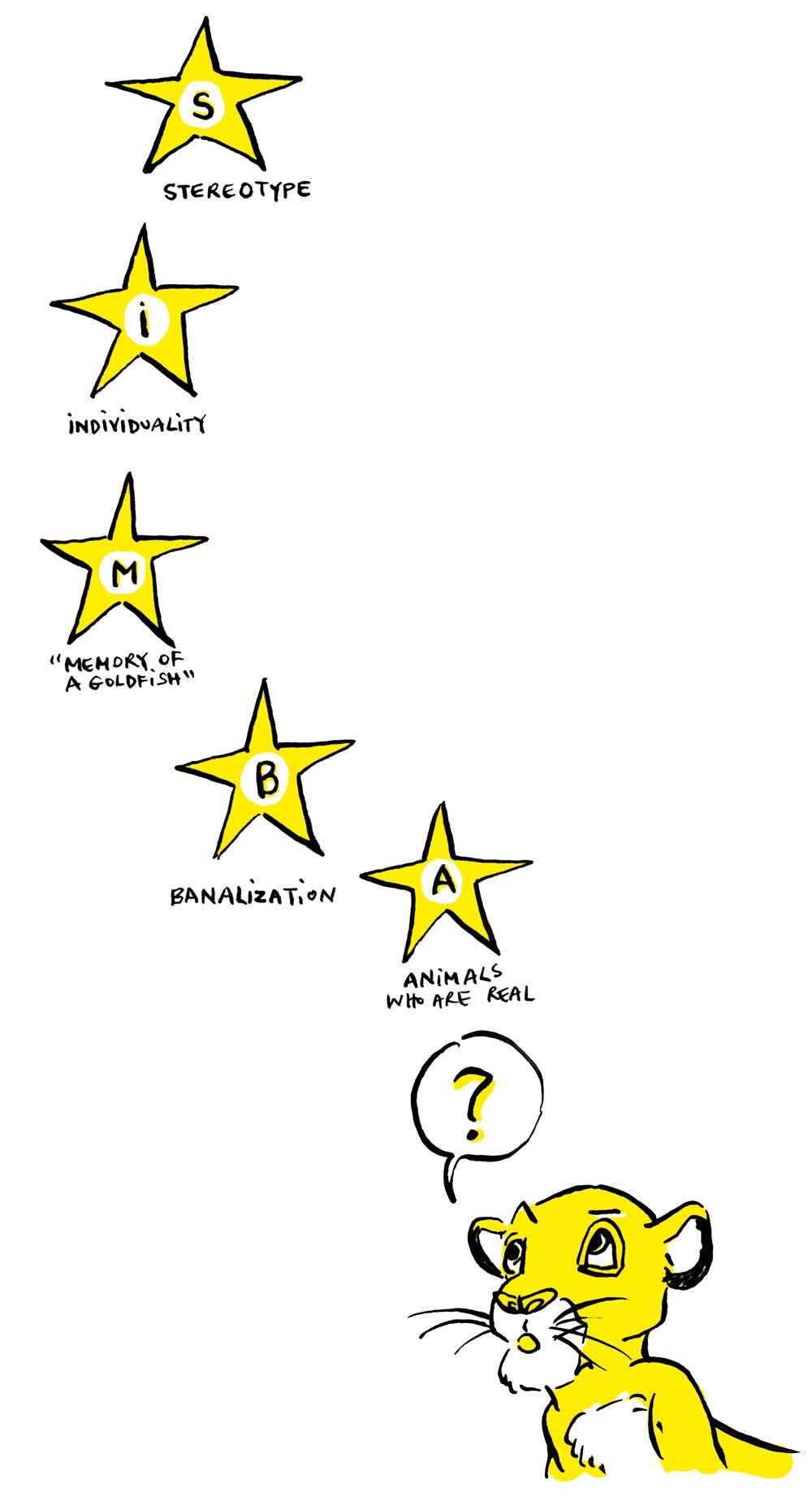

Let's call this test SIMBA – after the name of the hero of The Lion King – in order to easily remember the 5 axes of speciesism in fiction – Stereotype – Individuality – “Memory of a goldfish” - Banalization – Animals who are real.

S - Stereotype

Do the animal characters convey a stereotype, a cliché or a false character trait about their species? Donkeys who are stubborn, goldfishes without memory and sheeps who only follow? (all these examples are erroneous beliefs.)

Examples:

- In The Lion King by Disney, the hyenas are vile and mean, contributing to the reinforcement of that myth.

- Steven Spielberg's Jaws, showing a (fake) monstrous shark who was a predator of humans, had an immense impact on the reputation of those animals.

- In Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea, the marlin killed after a very long fight is described as a brave and dignified adversary, whereas the sharks who eat his remains at the despair of the man are shown as cowardly and vile.

I - Individuality

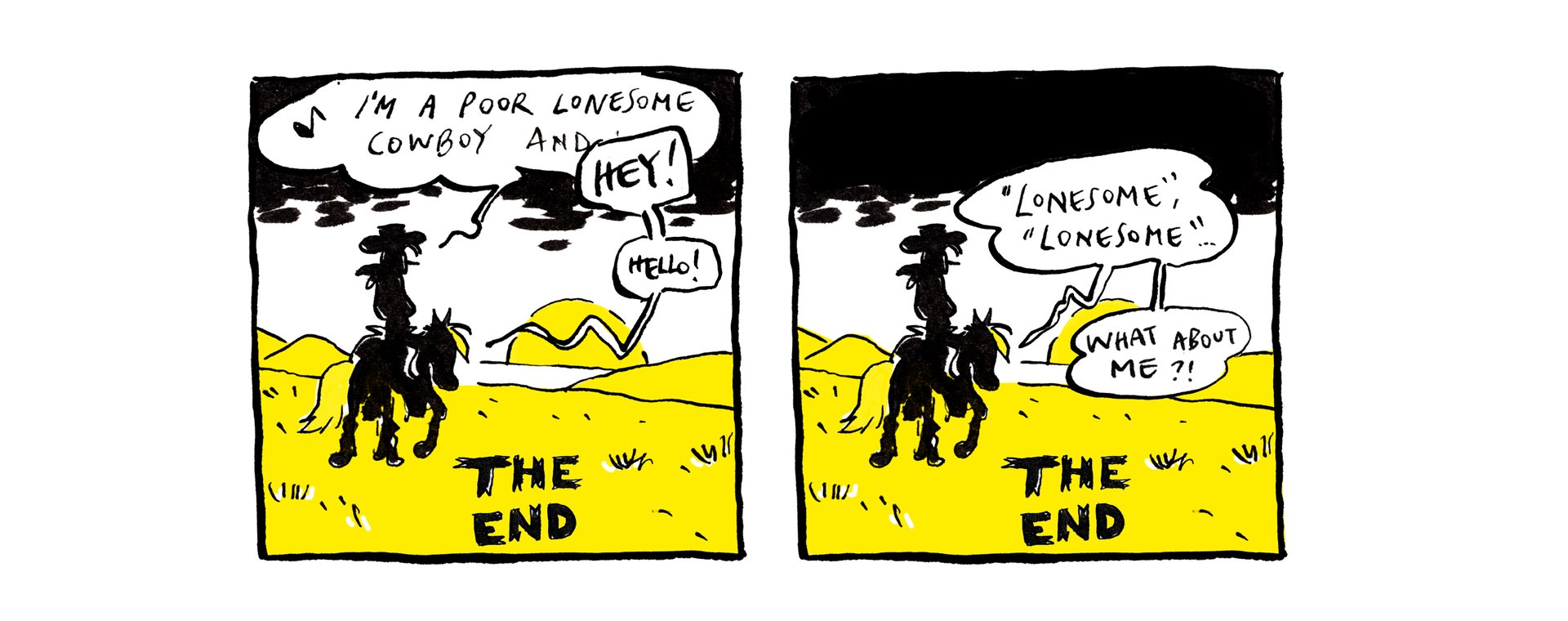

Are the animals deindividualized, without a personality of their own? Are the animals who are playing a role in the story just “a rabbit that happens to be there”, “the family dog” without personality of their own, generic, replaceable? Or are they characterized, with a temperament of their own, a name? Typically, in Westerns for instance, horses do not have names, do not have a story and are interchangeable.

Do they serve only the interests and objectives of a human character? Or have they been given an objective of their own, or even its trajectory, with its obstacles and its resolution? An extreme example of deindividualization, anthropomorphism[2] reduces the animal to a stereotype (often without any ground in reality, such as the reputation of pigs to be dirty) which serves to underline human character traits. It constitutes an appropriation of the image of a species so as to not say anything about the animals whose form is being appropriated.

Examples:

- In The Hound of the Baskerville by Arthur Conan Doyle, the canine who gives its title to the novel has no name, no characteristics, he is a sort of weapon or evil ghost manipulated by a human.

- In Disney's animated cartoon Robin Hood, all the characters of this perfectly human story have animal traits, which cliché associated to the species serves to characterize the part: the hero, slick, is a fox, the lady in waiting, energetic and comical, is a hen, the sherif, insensitive and mean, is a wolf, etc.

M - "Memory of a goldfish"

Is the language of the film speciesist? Is it contributing to maintaining discrimination through expressions such as “I have bigger fish to fry” (as if a fish's fate was always to be fried), “collecting specimens” (a hunting euphemism to say slaughter), “to be treated as cattle” (implying that what is unacceptable for humans is alright for animals), etc. In her essay The disdain for beasts, Marie-Claude Marsolier examines in detail this oppressive aspect of language.

B - Banalization

Is the work banalizing domination of animals?

Does it contain a representation of violence against an animal? Can we see in it animals who are beaten, forced, restrained, imprisoned, etc? We often don't have to look far in order to stumble upon the representation of a fishing trip, fishes in a tank, or a stag killed during a hunt, for instance.

Are the protagonists using a domination of animals which is banalized? Can we see them eating meat, wearing fur, riding a horse, owning a herd? Buying a dead fish, throwing eggs on someone, milking a goat, or sewing leather shoes? Reflecting the wide spread usage of animal products in our society, examples are practically endless.

Examples:

- In Hergé's comic book The Black Island, Tintin saves a gorilla exploited by bandits and... gives him to a zoo. No real gorilla suffered for these scenes, but the fact of surrendering an individual to a place of imprisonment (we can even see the gorilla cry behind the bars) is shown as an acceptable action and Tintin is not badly perceived for it.

- In Giant Mickey Parade #307, Scrooge McDuck (a duck...) is a sheep breeder and produces gloves from their wool, whereas Donald (also a duck) eats a sausage hamburger, without anyone raising an eyebrow.

A - Animals who are real

Is the work (audiovisual/stage only) using real animals instead of visual effects? Did the shoot require real cats, dogs, horses, cows, fishes, etc? Despite there being many sorts of training and making animals “play” for those productions, animal rights organizations[3] estimate that exceptions are not the rule and that it is not possible to reconcile this practice with the respect for the interests of the concerned individuals, for example making sure that the animal in question wouldn't have other priorities than doing what is asked of them, if they were free to chose how to lead their lives.

Example:

- During the filming of Life of Pi by Ang Lee[4] , the (real) tiger, King, almost drowned in a cistern.

As a consequence also of the speciesist pedestal of our society, it may be quite an achievement to manage to shoot a movie in exteriors without filming the doors of a creamery on a street, or cows on a field during a road movie. To each production and project its possibilities. The aim is not to conform to an ideal of purity, but to be aware of one's choices of representation. In books it is, on the other hand, possible to choose meticulously what is being said and shown.

Thus, the more the replies to those questions are affirmative, the more the speciesism is strong in the given work.

When the gaze is critical

If the story holds a critical gaze on the domination of animals, then the questions can have a positive reply without being speciesist.

Examples:

- In Okja, the movie by Bong Joon-ho, the slaughterhouse scenes (which only use computer generated animals) serve to criticize the difference humans create between animals they love and those they massacre.[5]

- This necessity can be found in Animalia, the novel by Jean-Baptiste del Amo, which describes in detail the horrors of the condition of pigs in a breeding farm in Normandy in order to denounce it.

As an exception to this, it goes without saying that if a work holds a critical gaze but uses violence on real animals during its creation, then it is indeed speciesist.

Horses in 19th century streets?

In one of my comic books, I was brought to drawing horses carriages. It was a historical fiction in which the animal condition was not a theme and in which almost no animal was visible. I am against the exploitation of horses, but I have estimated it was correct to show that horses were a pillar of mobility in those times, instead of hiding this aspect and risking to render the representation anachronistic. If this had been a movie, I would have demanded that the horses were CGI. This example nevertheless shows if not the gray areas of this test, at least the absence of universal rules in the matter and the necessity of thinking about different factors of creation.

A proposition in the form of an appeal

It is more than time to reach a further stage than just the certification no animals were harmed for movies, which is not enough at all[6] , only concerns american movies, and doesn't concern itself with the culture conveyed by the works.

The SIMBA test proposes an outline to help an evaluation and a despeciesization of our cultural creations. It probably calls for improvement, certainly to reflection and to discussion. Who doesn't remember a novel or a movie that profoundly impacted their life? Let's give the means to this power of fiction to create an impact which is not made at the expense of other animals, but, in the contrary, in a direction of a more just world for all sentient beings.

In practice of the test

The example of Ratatouille

The famous animated movie by Pixar/Disney which came out in 2007 tells the story of the rat Rémy, who dreams of becoming a chef at the gourmet restaurant Chez Gusteau in Paris, and who teams up in this goal with Alfredo, the kitchen assistant.

Ratatouille does surprisingly well at the SIMBA test. One might think that the concern of animal representation (and the so called “sewer” rats on top of it!) was present at the origins of the project:

S - Stereotype? The film conveys a positive image of rats, albeit subversive since it explicitly overthrows all the clichés associated with this species and manages to cause a decided empathy for the protagonist, Rémy, and his peers. There is a strong moment when Alfredo, after a fight, comes back to the kitchen of the restaurant (a highly sanitary place) and finds the entire colony of rats helping themselves to food in the pantry. He is shocked, but his shock is not linked to the species of these individuals, nor to the repulsion generally associated with them: “You are stealing food?! I thought you were my friend!” he cries. In no moment in the story is Alfredo underlining the difference between their two species. Furthermore, human cruelty towards rats is denounced in a very strong way in at least two scenes.

I – Individuality? All the non human animal characters are defined, have a name if they are more than background and have goals of their own, conflicts and trajectories.

M - “Memory of a goldfish”? If I am not mistaken, the movie does not have any language formulations at the expense of animals, and the “of course they ratted us out” at the end functions more like an ironic wink.

B – Banalization? Only the question of the banalization of the use of animal derived products poses a problem in the movie. As it surely would have been strange to see Rémy eat or cook other animals, we see him consume eggs and cheese, and except for one instance (the anonymous rat who “tenders” a steak with his fists, seen very quickly in a scene where all the rats share kitchen chores), we only see the preparation of vegetables, herbs, and other plant or at least vegetarian products. And it must be emphasized, of course, that the signature dish of the movie and of the rat chef, the ratatouille, is a dish without animal products. Nevertheless, the menu of the restaurant, omnivorous (including foie gras!), remains full of propositions of meats and fishes. It would have been possible, even easy, to integrate a critical gaze on this aspect of the restaurant, and to give Rémy, Alfredo and their close ones (SPOILER) a gained consciousness so that the bistro they open together at the conclusion of the story (and which is also a restaurant for rats) was a place without the use of animal or animal derived products.

A – Animals who are real? Ratatouille does not use any real animal.

Even though it is remarkable[7] , Ratatouille is then speciesist in its banalization (and even esthetization, on a smaller scale) of the use of non human animals in food.

For further exploration

Bechdel Test, article on Wikipedia.

The Cinema of Animals, Camille Brunel, UV editions, 2018.

“Animal gaze”: what if you took on an animal gaze? Article by Marjorie Philibert for Le Monde, March 16, 2024.

The Disdain for “beasts”: a lexicon of animal segregation, Marie-Claude Marsolier, Presse Universitaires de France, 2020. L'Amorce journal propose a presentation and excerpts from it.

Revelations on the animal wrangler star of the movies, video investigation by Vakita.fr, November 16, 2022.

“I don't want to kill this whale!”: vegans, even in video games, article by Clémence Kerdaffrec for Le Parisien, April 19, 2024.

Fanny Vaucher is an illustrator and comic book author, known among other works for Le Siècle d'Emma and Les Paupières des poissons. She is active in The Observatory of Speciesism since its creation.You can write to her about this article at fanny.vaucher@observatoireduspecisme.ch

Jola Cora is an actress, writer, director and animal rights activist, author of the antispeciesist fairy tale Ataraxia.

Notes

-

^

1. Are there at least two female characters whose names we know? 2. Do they talk to each other at some point in the movie? 3. If yes, do they talk about something other than a man? These questions, having since become a point of reference, have had their limits discussed, and there exists today many models and variants. (Bechdel test, on Wikipedia.)

-

^

Widely used in graphic novels and cartoons, anthropomorphism gives animal physiognomies to the characters and often attributes to those characters stereotypical traits associated to the given species (the majestic lion, the placid cow, the modest mouse, etc.)

-

^

For example, “The message of PETA destined to all producers is that they have no idea what is happening outside of the set, so the only way to make sure a movie is produced in an ethical way is to do it without animals.” on the website of PETA France. The association PAZ (Projet Animals Zoopolis), on the other hand, calls for a whistleblowing for all so called “wild” animals used in French cinema.

-

^

Yet a movie full of computer generated images of animals and whose antispeciesist vocation makes remarkable in many ways. See Camille Brunel's study of it in The Cinema of animals.

-

^

"The film itself might have been purely whimsical had Bong not emphasised the story’s harsher elements, including a sequence set in a slaughterhouse. "Films either show animals as soulmates or else we see them in documentaries being butchered. I wanted to merge those worlds. The division makes us comfortable but the reality is that they are the same animal”, explained director Bong Joon-ho in The Guardian.

-

^

As we can imagine, the certification that no animals were harmed during the making of this film does not concern the many animals killed to feed the crew during the weeks of shooting. Besides, the vast majority of animals appearing on the screen are probably those who appear on a plate and are eaten by the characters.

-

^

Remarkable only when it comes to non human animals, because this movie fails the Bechtel test dramatically.